Women on the Verge: Volume Five – Gathering and Evaluating Ideas

No one religion can console this enormous country.

No single philosophy convince it.

No therapy relieve it of its burdens.

No legal system comfort its injustice.

No medicine deliver it from pain.

No government give it joy.

Only art does that.

– playwright Romulus Linney

Vol. 5: Gathering and Evaluating Ideas

NOTE: Before reading this posting, please make sure you’ve read Women on the Verge: Volume Four, which outlines the entire creative process. Otherwise, the following may be confusing, rather than helpful.

Preparation Stage: Blocks (Challenges) and Tools

Progression through the creative process is rarely a straight march. It’s more like a yellow brick road, with curves and sidetracks to deal with unexpected situations. Just like Dorothy’s friends we, too, need a working brain, a heart that believes in possibility, and a lot of courage. The Preparation Stage is in two parts: Gathering ideas and Evaluating ideas. Each presents different blocks, and these require different tools.

Part I: Gathering Ideas

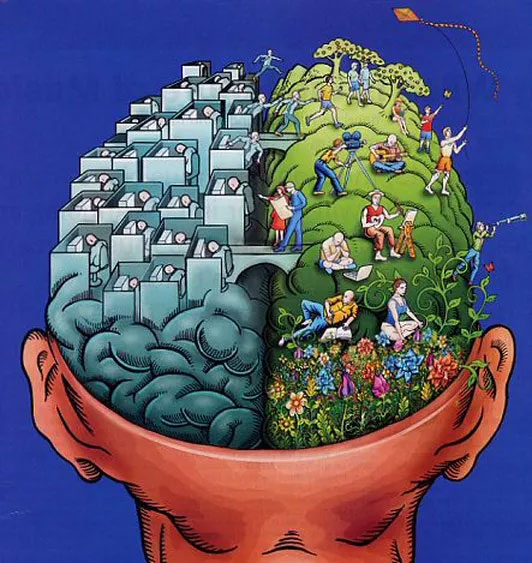

This is your imagination unleashed. Unfettered as it gathers momentum. It occurs in your right-brain, where multiple bits of information are processed simultaneously, like a kaleidoscope. The aim is not to get stuck in the obvious, but rather, to engage the novel and inventive. Another term for this mindset is “divergent” thinking. Divergent thinking involves: a willingness to question assumptions (“Why not?”) and be receptive to all ideas without censorship. This requires you to remain mentally open, tuning out your inner critic, and suspending judgment. As ideas arrive, hold an attitude of possibility (“What if?”) while focusing on QUANTITY. The goal is to increase your options by making unusual connections and allowing ideas to build on each other. Exercising what is known as “cognitive flexibility.” In order to achieve all this, the most important thing you can do is stay out of your own way.

Common Creative Blocks

Block #1 “Blank Canvas”

The writer stares at a white screen, the designer is uninspired. They wait but nothing comes. This is more common when a project is not born out of passion, but is externally driven by a professor or an employer. These projects have hard deadlines, as well (unlike your personal projects). When there is no external direction, and the subject, focus, form, etc. are in the hands of the artist, there is a lot of freedom. To risk-aversive artists too much freedom means an even greater chance of making mistakes. Externally-directed parameters serve as a sort of protection/safety. Without these, they freeze up. Whereas, risk-embracing artists buck against all that external control. In either situation, when no ideas arrive frustration sets in. The harder they try, the more frustrated they are. Unable to type that first word or make that first stroke, or gesture, or sound, the project can die in utero.

Block #1 Tools

Attitude adjustment. Replace your demand for certainty with “curiosity.” Stop expecting ideas to appear fully formed, ready to be applied. Just “allow” them in whatever state they appear. Imagine someone holding a newborn and saying, “This won’t do. She doesn’t know how to drive.” You have to let ideas develop. For now just jot them down or sketch or whatever. In Zen philosophy this is known as “Beginner’s Mind.” Empty mind. Remember the goal at this stage is quantity not quality. For your brain to remain in production mode, you can’t keep stopping the conveyer belt each time you think, “That won’t work” or “That’s a stupid idea or “That’s already been done.” This is NOT the time to focus on the unique and reject the obvious. What if all “obvious” needs, in order to become “interesting,” is the right pair of shoes? Or a limp?

Block #2 “The Myth of Limited Ideas”

This is when an artist goes forward with one that “will do the job” but does not excite. Usually it’s the first idea. This often happens after struggling with “Blank Canvas”. (Especially if a deadline is involved.) The fear is that another one won’t come along. It’s like marrying the first person who asks you out, just so you won’t be alone, rather than waiting for a better match. Especially vulnerable are those who procrastinate, shrinking the amount of time available to explore alternatives. First-idea work will almost always bore you and end up being disappointing to all. What we have here is a trust issue; when an artist doesn’t expect the creative process to deliver on its own, without her being able to control all aspects. Unfortunately control makes innovative flow impossible. It’s like driving with the brakes on.

Block #2 Tools

Use a creative project’s requirements and parameters as a skeleton, fleshing it out with your senses: Observe your daily environment without judgment: Listen, taste, touch and smell. Pay attention to what draws you toward it, tweaks your curiosity. Look for patterns, themes. Whose work repeatedly attracts or inspires you? Try to capture what that essence is. How would that translate to your voice or style? (To create authentic, interesting work, be sure you understand the difference between inspiration and mimic.)

Block #3 “Premature Evaluation”

As each idea captures your awareness, it is immediately rejected. Self-talk is usually, “That’s stupid,” and “That won’t work,” and “That’s not interesting.” This is the voice of your inner critic. It plays an important role in the creative process, but NOT until later. If you allow it to dominate this early, you will generate very few ideas. Your inner critic has an opinion on everything, and sometimes those opinions are valuable. It’s just bad timing when it pops up there.

Block #3 Tools

Start out with good manners. You don’t want to slam the door on an opinion, just because it arrived too early. When you “hear” your first negative comment, offer up a simple, “Later.” If that doesn’t work, escalate to, “NOT NOW!” Post a sign in your work area: “All Ideas WELCOME! Opinions Must Wait Outside.” Make sure you save each idea. You’re not rejecting it; you’re rejecting the opinion.

Block #4 “Keeping it Safe”

This is the rejection of workable, innovative ideas, because they scare you. These ideas take you outside your comfort zone: the concept is too bizarre or the materials are too unorthodox or foreign to you at your current level of expertise. Ideas (political, sexual) may also be rejected, because they cross a line and challenge your deeply-held personal beliefs. Or, you want to avoid potentially-negative attention in general.

Block #4 Tools

A single idea might be too scary by itself. So write each idea on a Post-It that you can later move around, combining and re-combining in new ways. As each idea arrives, try using a “ladder of abstraction” by asking “What if?” “Why not?” Choose two random aspects of the project and create a relationship between them. Do it again, then “mate” the products of those. REMEMBER: The objective is to create interesting “offspring,” while on a high-wire, without a net. When an anxiety-producing idea comes to you, immediately stretch it far enough to find at least one strength in it – even if itseems lame at the time.

As for fear of negative feedback, highly original, successful artists know that innovation REQUIRES risk, and risk triggers anxiety. The problem is: Avoiding anxiety diminishes creativity. If you want your work to be noticed, then being uncomfortable during certain stages comes with the territory. To stand out, you have to draw attention. Many writers, for example, live quiet lives, off of social media. Introverted by nature, their dream is also their nightmare; a best seller would thrust them into the spotlight they work hard to avoid. (The result is a lot of brilliant novels and plays stored in boxes under beds.) The best tool is to face risk-aversion directly with support from other artists.

Part II: Evaluating Ideas

In Part I of Preparation Stage, the emphasis was on generating without thought to quality. Now quantity pays off. (If you posted the aforementioned “Welcome!” sign, it’s time to take it down.) Part II is all about reviewing, weighing and evaluating. This means you’re shifting to your left-brain, which works in a linear fashion, processing one piece of information at a time. This is where your “critical eye” reigns supreme, but don’t confuse critical with “negative.” An idea might have merit, but not be applicable to your current project. Determining the value of an idea is a skill that for some is immediate; for others it takes years to master.

The primary skill needed here is the ability to throw away ideas. When a mediocre idea is tossed, that makes room for a more inventive one to jump to the front of the line. But when you hold onto a mediocre idea for security reasons, it will actuallyblock traffic flow. Research has shown that the main difference between regular creative people and those who are considered highly creative is this: Highly creative people throw away more ideas.

Also needed, when evaluating, is a kind of thinking known as “convergent.” (opposite of “divergent,” needed in Part I) Convergent thinking is what we refer to as our “critical eye.” Before, it was a hindrance. Here it is an asset. Another skill is the ability to refine or improve on an idea that has potential, but isn’t quite useful yet. It’s also important not to get lost in a myriad of ideas. Focus on one at a time. Finally it will make the process go more smoothly for you if you design a rational process for eliminating ideas that you are emotionally attached to. Remain focused on your current project, but – as mentioned before – keep a record of any idea that rises above mediocre. Some might be perfect for future works.

Block #5 “Analysis Paralysis”

It seems like you’re working, but rather than forward progression it’s more circular. You go over and over the ideas you’ve generated but aren’t able to commit to one. Like several other stages in the creative process, this one is a struggle for left-brain artists, who freeze at decision-making for fear being wrong. You get stuck and can’t make the leap from the safety of the present (known) to the future (unknown). You stay where you are comfortable (critical thinking) rather than allow the anxiety that comes with committing. You’re well aware that a jump into your own potential will bring you closer to eventually being evaluated by others.

Block #5 Tools

If you can’t commit to an idea, then commit to a decision deadline. In the space between now and that deadline, rank the ideas you have into three groups: most interesting (inspire you the most), somewhat interesting (you could get inspired by these), and last, not interesting at all. If you aren’t inspired no one else will be either, so toss the last group immediately, unless you imagine a future where they might grow. When you have at least three that inspire you the most and three that somewhat inspire you, write each on a slip of paper and put these six in a container and set them aside. (This is a physical exercise that mimics what your brain will be doing while you shower or run or sleep.) Pick a date before your deadline or — if you seriously procrastinate — a time on deadline day. Open the container and randomly pull out a slip, read it and write down anything it triggers. Do this with each slip. Then begin pairing them while jotting reactions for each new configuration. You will not get what you truly want; a guarantee does not exist. But you will get what you need: enough information to select the solution that interests you the most and inspires you enough to begin the work.

Block #6 “Rehearsing Disaster”

You’ve finally committed to an idea, but you’re not invested in moving forward with it. Your attitude is “Why even start? What’s the point?” So, now the issue has moved from not having an idea to not trusting your ability to carry through to the end. Once a negative and fixed mindset takes hold, it’s difficult to shake loose. It’s like a virus, traveling back and forth through all the stages of the creative process. Creative thinking and action has been taken over by a sense of threat and a defensive response. You’ve abandoned your rational left-brain and are stuck in an emotional swamp. Your right-brain – where you give birth to ideas – is also where you imagine creative failure.

Block #6 Tools

Don’t let your imagination do a “drive-by.” When images of future disappointment, humiliation, and shame strike, dive into your left-brain and take them to court: Ask yourself, “Where’s the evidence this will happen? What’s that outcome based on? What is a possible alternative scenario?” The next tool is to simply keep asking yourself one important question. It only works, if you force yourself to truly dig for a response each time. You can’t say, “I don’t know.” If an answer doesn’t come immediately, then keep sitting with it, until one does. Remember, it’s not that you are trying to predict the actual future. You’re simply trying to understand why your mind is fighting to keep you “safe” from the very future you dream of. Your answers will range from true possibilities to incredibly absurd outcomes. So, what is that question to pursue like a bloodhound? After a negative self-prediction, ask “And then what will happen?” Ask it over and over shortened to: “Then what?” Each time offering the answer that feels most authentic for your individual situation. The bottom line is definitely primal and fairly universal, but I’ll let you discover that yourself.

Something to Think About

We’re not only jumping back and forth through the stages of a single project, but often find ourselves juggling more than one project at the same time. And, these are usually in different creative stages. A few months ago I was experiencing: Preparation/Incubation Stages for this blog, generating and evaluating potential topics. This was quickly followed by an Illumination Stage “Yes!” when “Women on the Verge” popped into my head for the title. A memoir was deep into the Transformation Stage, bogged down in the Self-Evaluation Stage and is currently spinning in Modification mode, while I try to develop a better way to knit the chapters together while maintaining the flow. Finally, a screenplay, was headed to Public Evaluation, back to a producer, who had made a couple of suggestions to increase its appeal to a wider audience.

Each stage in the creative process brings its own challenges and triggers different forms of anxiety with corresponding coping mechanisms. (Some more affective than others.) But that’s the deal: If you “dabble” in the Arts, you have the luxury of stepping away from your work when it no longer amuses or it becomes too challenging. But … if you are in it for the long run, because you are driven and can’t imagine not writing or acting or painting or singing, then you don’t get to step away. You are an artist. You step straight into the fire.

Questions for Consideration

1. How has your art shaped who you have become?

2. What are five words you would use to describe your style?

3. How much validation do you need for your work? From whom?